01 Aug 2025

The Great Firewall Report, a “long-term censorship monitoring platform”, just published an analysis of how the “Great firewall” handles QUIC. I found that a very interesting read.

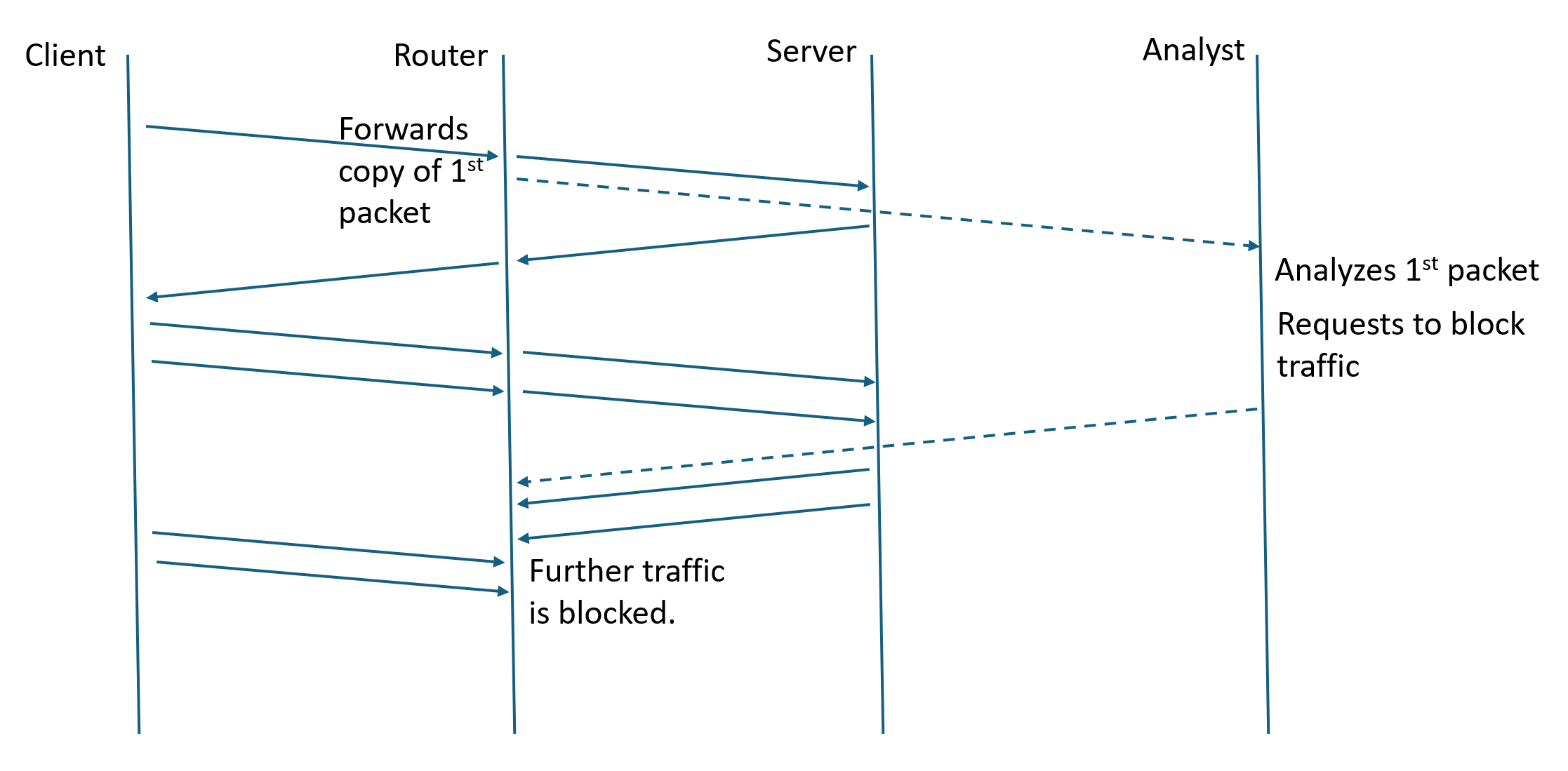

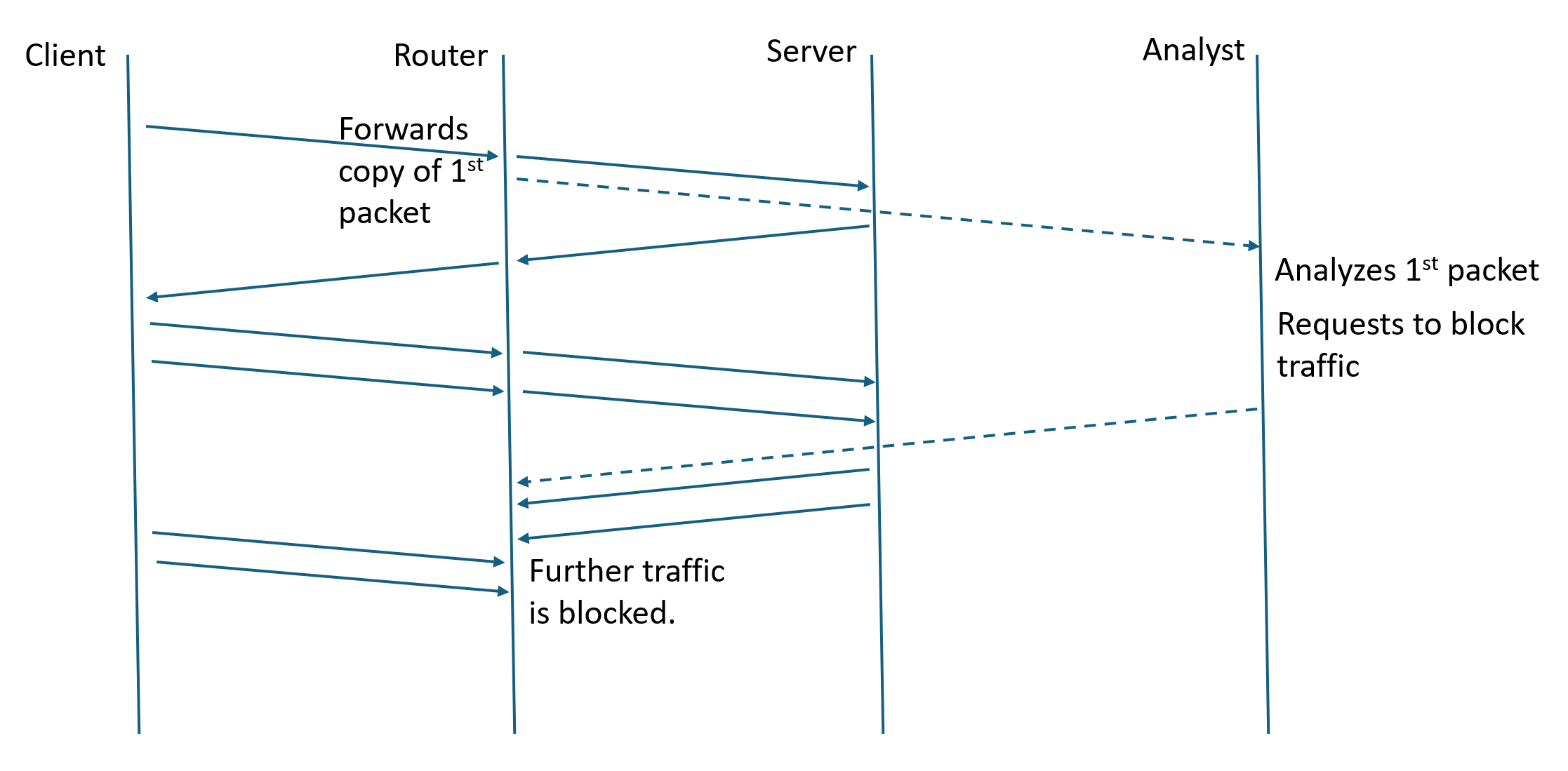

The firewall work is distributed between an analysis center and cooperating routers, presumably at the “internet borders” of the country. The router participation appears simple: monitor incoming UDP flows, as defined by the source and destination IP addresses and ports; capture the first packet of the flow and send it to the analysis center; and, receive and apply commands by the analysis center to block a given flow for 2 minutes. The analysis center performs “deep packet inspection”, looks at the “server name” parameter (SNI), and if that name is on a block list, sends the blocking command to the router.

The paper finds a number of weaknesses in the way the analysis is implemented, and suggests a set of techniques for evading the blockage. For example, clients could send a sacrificial packet full of random noise before sending the first QUIC packet, or they could split the content of the client first fly across several initial packets. These techniques will probably work today, but to me they feel like another of the “cat and mouse” game that gets plaid censors and their opponents. If the censors are willing to dedicate more resource to the problem, they could for example get copies of more than one of the first packets in a stream and perform some smarter analysis.

The client should of course use Encrypted Client Hello (ECH) to hide the name of the server, and thus escape the blockage. The IETF has spent 7 years designing ECH, aiming at exactly the “firewall censorship” scenario. In theory, it is good enough. Many clients have started using “ECH greasing”, sending a fake ECH parameter in the first packet even if they are not in fact hiding the SNI. (Picoquic supports ECH and greasing.) ECH greasing should prevent the firewall from merely “blocking ECH”.

On the other hand, censors will probably try to keep censoring. When the client uses ECH, the “real” SNI is hidden in an encrypted part of the ECH parameter, but there is still an “outer” SNI visible to observers. ECH requires that client fills this “outer” SNI parameter with the value specified by the fronting server in their DNS HTTPS record. We heard reports that some firewalls would just collect these “fronting server SNI values” and add them to their block list. They would block all servers that are fronted by the same server as a one of their blocking targets. Another “cat and mouse” game, probably.

If you want to start or join a discussion on this post, the simplest way is to send a toot on the Fediverse/Mastodon to @huitema@social.secret-wg.org.